The Birth of Modern Independent Watchmaking: How Two Groups of Watchmakers Redefined an Industry

How two movement development laboratories became the breeding grounds for modern independent watchmaking, The Opus Project, and the birth of modern independent watchmaking

“For a lot of people, being independent means putting your name on the dial. For me, being independent is being able to do all your components, do all of your construction, make your own watch, train your team, create a workshop that makes watches, not needing to use many suppliers, but being able to conceive completely what you do. And afterwards if there is someone else’s name on it, what is the problem?”

-Luca Soprana

During the quartz crisis of the 1970s and early 1980s, the fates of Swiss watchmaking and the entire mechanical watch industry were on the brink of disaster. The battery-powered quartz watch, both less expensive and more accurate, had rendered the mechanical timepiece unnecessary. The demise of the mechanical watch seemed written on the wall.

From this existential chaos, a renaissance emerged. Fueled in no small part by two boutique movement workshops, a new generation of horological visionaries cut their teeth and learned to carry on the legacy of haute horology. Finding freedom in the newfound superfluity of the wristwatch, these watchmakers realized their creations no longer had to exist solely for timekeeping. Rather, their creations could become wearable works of art, mechanically complex items that not only expressed a specific point of view on watchmaking, but pushed the limits of human ingenuity and micro-engineering.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, two firms in particular incubated the talents of young watchmakers, and accelerated the careers of many of today’s best-known independent watchmakers. Those two firms were Audemars Piguet, Renaud, et Papi, better-known as Renaud et Papi or APRP, and Techniques Horlogéres Appliquées, or THA.

Both workshops were created by groups of incredible young watchmakers who recognized the structure of the Swiss watch industry was broken. The bureaucracy of the major brands dictated that young watchmakers paid their dues by doing 20 years of simpler work before working on a complicated watch. For those looking to skip the corporate ladder, there was no better place to work that APRP or THA.

But the watch industry did not change overnight. It largely remained an industry unchanged from the days of Calvin — watchmakers outside of the large brands developed movements and parts for them, crafting and creating so that large brands could industrialize their production. While the creation of small parts was once outsourced to farmers and shepherds, the innovation and creation of new ideas and concepts was outsourced to small workshops across the country.

Following the growth of these workshops, Harry Winston partnered with independent watchmakers to bring forward the best of high jewelry and independent watchmaking, partnering with a number of independents and helping them to gain exposure to a broader market.

The Dreamers

The revolution began in 1984 when two talented young watchmakers met in the skeleton workshop at Audemars Piguet. They would challenge the norms of the watch industry, raise a generation of independent watchmakers, and shape the world of modern watchmaking.

They were Dominique Renaud and Giulio Papi, of Renaud et Papi. In the industry structure of the time, both of them would have to wait close to 20-years to work on a complicated watch. They didn’t want to wait. They wanted to work on those watches early in their careers so that they might build skills, develop new solutions, and innovate.

So what did they do? They left Audemars Piguet in 1986 and opened their own shop, to give themselves the opportunity to work on complicated watches. Renaud et Papi was born.

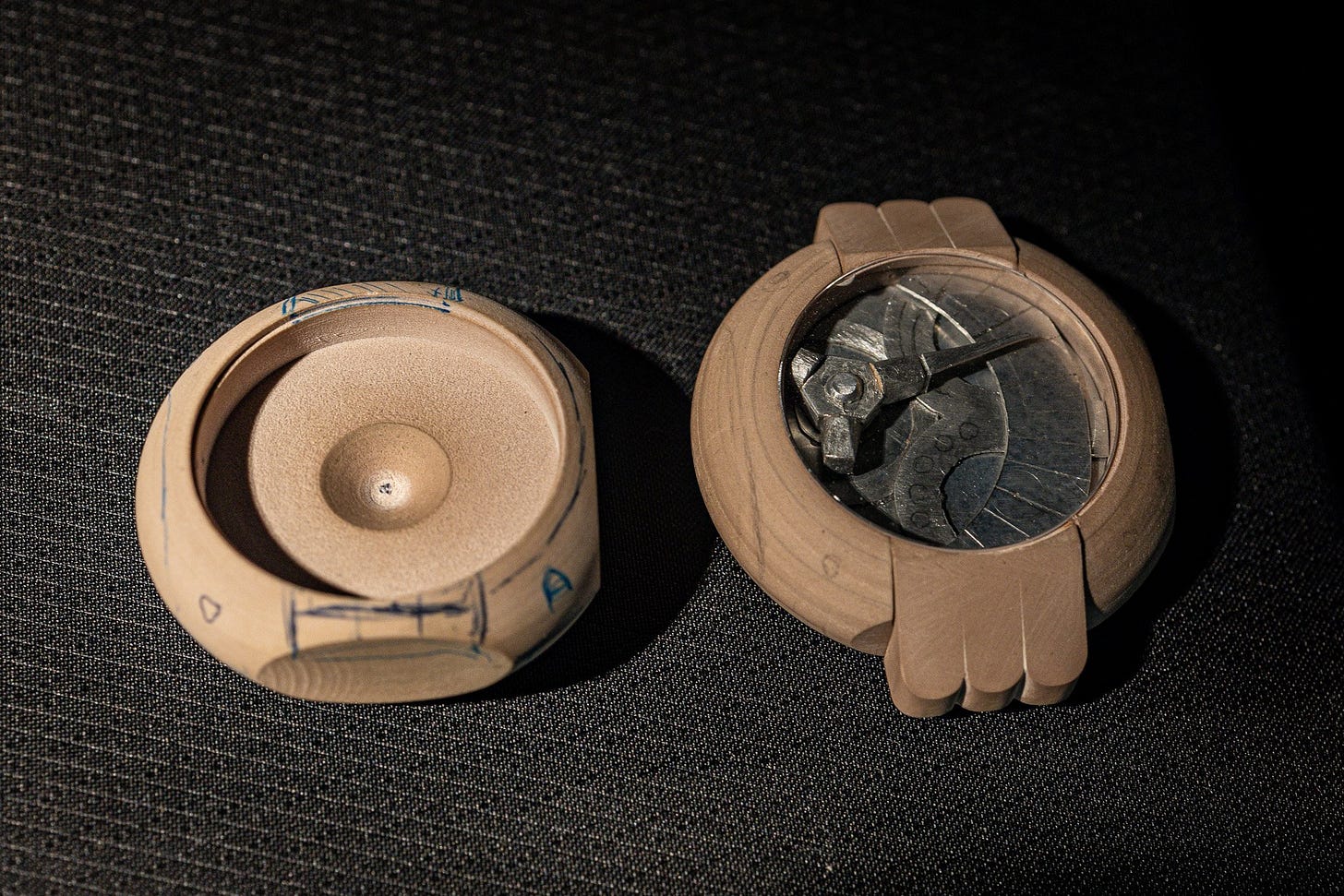

The duo focused on new technologies and new materials with the goal of engineering new complications. Pioneering the use of computer-aided design allowed them deeper access and understanding of the world of microtechnology engineering, helping Renaud and Papi build several minute repeaters and understand complications in greater detail.

The duo worked alongside Christophe Claret, another independent watchmaker focused on repeating watches for a short stint, and would receive an injection of capital in 1992 from their former employer, Audemars Piguet, also a client, to keep the doors open and continue to push the limits of horology. From Audemars Piguet, Renaud, and Papi (APRP), a renaissance began.

APRP served as an incubator for young talents. Notable APRP watchmakers included Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey, who joined APRP in 1990 and 1992 respectively. They went on to found Greubel Forsey and push the limits of complications and chronometric precision. Tim and Bart Grönefeld, founders of Grönefeld: The Horological Brothers, were also among the distinguished alumni, joining APRP in 1992 and 1995 respectively, leaving in 2008 to start their eponymous brand.

Other notables include Carole Forestier-Kasapi who led Cartier’s movement development until 2020, and now leads movement development for TAG Heuer. Peter Speake-Marin left to create his brand with co-founder Daniela Marin, and he continues to share his love of watchmaking and deep industry insights with his project, The Naked Watchmaker. Other notable alumni now working as independent watchmakers include Anthony De Haas, Stepan Sarpaneva, and Andreas Strehler.

This was the dream team of watchmakers. From the workshops of APRP a movement was born. These Watchmakers completed many minute repeaters and high complications for brands, and notably worked on the launch of Richard Mille. At their prime, they produced some of the most spectacular watches the watch world has seen, many of which we may never know because of rigidly enforced non-disclosure agreements.

APRP was founded at the right time, attracted the right talent, and provided young and disruptive watchmakers with a chance to hone their skills and challenge the traditions of the watchmaking industry. This philosophy helped many young watchmakers develop their skills in design, prototyping and building complications, providing them with all the skills they would need to eventually become independent watchmakers.

Techniques Horlogères Appliquées (THA)

The second powerhouse workshop at this time was Techniques Horlogères Appliquées, founded in 1989 in Sainte-Croix by François-Paul Journe, Vianney Halter, and Denis Flageollet. The trio of watchmakers were young and hungry to learn. They were ambitious in creating a laboratory that would allow them to work together on a shared creative vision, making watches of their own original designs. THA focused on creating movements for Cartier, Breguet, Girard Perregaux, and Carl F. Bucherer, but many of these projects remain under strict non-disclosure agreements. As a result, the general public may never know the true extent of their work.

THA was behind the creation of the 1990 Breguet Sympathique mantle clock, a clock that could hold and wind a Breguet Classique Complications wristwatch when docked to the clock. We also know that it was Denis Flageollet’s idea to make the Chronograph Monopoussoir as an homage piece to the Cartier Tortue CPCP that spurred the reboot of the Cartier Monopoussoir CPCP.

During this time, aside from Journe, Flageollet, and Halter, the company hosted many notable craftspeople, including Nicolas Court, a micro-mechanical engineer, who would later set up Janvier S.A. alongside Vianney Halter, and Pierre-André Grimm, a specialist maker of mechanical singing birds.

Vianney Halter left the company in 1998 to exhibit his Antiqua at the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI) Baselworld booth. The Antiqua would change how watchmakers and collectors thought about case shapes and case design, using multiple subdials for the perpetual calendar in a case that was equal parts steam locomotive and science fiction. At THA Halter worked on pieces for Franck Muller, Jaquet-Droz, Audemars Piguet, Mauboussin, Harry Winston, Breguet, and Zenith before becoming an independent watchmaker. This exposure to a broad variety of design aesthetics is clear in Halter’s work as he focuses on geometric shapes and complications.

François-Paul Journe followed Halter and exited in 1999, building his own brand through Souscription pieces as Breguet did, selling a limited edition series to collectors to fund his workshop. Journe’s fascination with the tourbillon began while apprenticing for his uncle’s repair business, and he was drawn to the complication. There was nothing on the market that he could afford, so he chose to build his own. It was this obsession with the tourbillon that launched his brand and helped him become arguably one of the most sought-after independents in the watch industry.

Denis Flageollet left THA in 2002 to join former THA client, David Zanetta, to launch De Bethune. His first watches at De Bethune showcased his technical genius while relying on Zanetta for the aesthetic design queues that skewed towards vintage watches. When David Zanetta stepped aside, Denis was able to express his incredible skills as a watchmaker and develop watches that are representative of his science fiction and nature inspired design, with incredible innovations. Denis continues to innovate on the work of the great master watchmakers with a specific focus on materials innovation, escapements, and balance wheels. Denis holds a double digit number of patents for mechanisms and micro-mechanical parts.

All three founders became well-known independent watchmakers, and both François-Paul Journe and Vianney Halter became members of the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI).

It’s not difficult to appreciate the work of both Audemars Piguet, Renaud, et Papi, and Techniques Horlogéres Appliquées S.A. Their teams created a number of amazing watches that we know of, and likely some amazing watches that we may suspect, but never know the full truth. These laboratories built incredible teams of watchmakers, accelerating their careers so that they would grow to become the modern independent watchmakers.

In some ways, this was destined to happen. Young watchmakers were disillusioned with the long waiting period before getting to work on grand complications and create something from scratch. What these young watchmakers accomplished was something tantamount to saving the industry following the Quartz Crisis and securing the future of the wristwatch. It is exciting to think that the independent watchmakers who emerged from APRP and THA are mentoring and inspiring the next generation of independents.

Along Came Opus

Harry Winston, renowned for its exquisite jewelry and precious gems, embarked on a transformative journey in 1998 to breathe new life into its watch department. With a thirty-one-year-old Maximilian Büsser at the helm, who later went on to establish Maximilian Büsser & Friends, the Opus Project would come to define the early era of modern independents.

Büsser’s mandate was clear: elevate the watchmaking to match the quality and reputation the rest of the brand was known for, and grow the business. “For me, it was only possible by creating a watch product which would approach the same level of excellence in watchmaking as Harry Winston already had in the world of jewelry,” said Büsser.

The Opus Project came to define an era of independent watchmaking. It pushed the boundaries of what most people thought possible for a traditional brand like Harry Winston and was completely unexpected. It was an innovative decision that spurred creativity, collaborations, and increased the visibility of independent watchmakers and shed light on the watchmakers, and the power of collaboration in an industry that remained resistant to change.

A chance encounter between Maximilian Büsser and François-Paul Journe at Baselworld in 2000 ignited a creative movement that would come to define the project. The Opus Project provided a platform for independent watchmakers to collaborate with Harry Winston Rare Timepieces, creating limited edition timepieces that would showcase not only their skills, but their personal vision of horology.

Collaborating with Harry Winston increased the reach of these independent watchmakers, exposing their work to a broader audience of collectors both in and outside of the watch world. Some of these watchmakers were already working for Harry Winston behind the scenes on new timepieces, and the Opus Project allowed them to showcase their work and co-sign the dial.

With François-Paul Journe as their inaugural collaborator, Harry Winston Rare Timepieces embarked on a mission to advance the cause of independent watchmaking, showcase innovations in watchmaking, and have an industry-wide impact in both creativity, the approach to sales, and acknowledgement of the artisans behind the timepieces.

Harry Winston and the Opus Project also asked independent watchmakers to change the status quo with their collaborations. Opus focused on new complications, new ways of looking at classic complications, and interesting movements. In this regard, Opus combined horological ingenuity with Harry Winston’s amazing metals. The metal of choice for Harry Winston jewelry was platinum, and the series began using platinum for Opus I-V, with Opus III and Opus V being offered in red gold. It was not until Opus VI that Harry Winston began using white gold for their cases. The Opus Project also leveraged Harry Winston’s superb gemstones, resulting in singularly stunning timepieces that would come to define gem-set watches.

The Opus Project’s emphasis on creative expression through limited edition timepieces revolutionized the industry. Each series was produced as a limited edition, something that both larger brands and modern independents emulated with great success. These watches remain highly coveted as early examples of many modern independents' work, making them sound investments in the watch industry because of their rarity, provenance, and the significance of the Opus Project.

The impact of the Opus Project reverberated throughout the watch industry. First, it lifted the veil of secrecy from those independent watchmakers who worked behind the scenes to develop new watches, allowing them to proudly sign their creation and be recognized for their talents. Through the power of collaboration, the Opus Project helped many independent watchmakers establish themselves with a broader audience, and in turn build their brand.

Harry Winston turned that soft power into a superpower, shining the spotlight on independents, and restoring humanity to watchmaking. By showcasing the talents of individuals alongside the talents of the Harry Winston team, Harry Winston fostered a supportive environment for independent watchmakers, normalizing independent watchmakers launching their own brands with unique horological visions.

Though Büsser would leave Harry Winston in 2005, the project carried on. According to Maximilian Büsser, The Opus Project’s greatest victory was to:

“bring humanity back into watchmaking. In the late nineties, most brands were competing to grow and become major actors in the industry, and we had started to forget about the actual people who engineered, crafted, and assembled the pieces. It was the beginning of the marketing era. Opus finally gave an amplifier and loudspeaker to these incredibly talented watchmakers who had virtually no voice – there was no social media in those days…”

The Opus Project was one of daring. It challenged the conventions of an industry that was rooted in tradition. It revolutionized collaborations, demonstrated what could be achieved with new voices and fresh perspectives were given room for artistic expression. In an era before social media, Harry Winston provided independent watchmakers a platform to share their skill, their vision, and their creations with the world.

The Opus Project in Order:

Opus 1 with François-Paul Journe

Opus 2 with Antoine Preziuso

Opus 3 with Vianney Halter

Opus 4 with Christophe Claret

Opus 5 with Urwerk

Opus 6 with Greubel Forsey

Opus 7 with Andreas Strehler

Opus 8 with Frédéric Garinaud

Opus 9 with Jean-Marc Wiederrecht

Opus 10 with Jean-François Mojon

Opus 11 with Denis Giguet

Opus 12 with Emmanuel Bouchet

Opus 13 with Ludovic Ballouard

Opus 14 with Franck Orny and Johnny Giardin

The Future

The Opus Project would set a standard for independent watchmaking that has received a lot of attention over the last few years and the auction results speak to the interest in the collaborative pieces from Harry Winston. It hasn’t gone unnoticed almost foreshadowing of what’s happening today and what LVMH seems to be working towards.

While Max believes that the Opus Project restored humanity into watchmaking, I worry about the future of independents and big brand collaborations. What Opus did was the first time that concept horologists, usually behind the scenes, were allowed to sign their name on the dial. Opus changed the game and helped to elevate these independent artisans and expose them to a broader market.

What Opus did was to uncover a playbook - one of working alongside talented artisans and watchmakers to put their work on display. In some sense, Max has gone on to do this with MB&F, and Simon Brette does this in his work. It has long been rumored that LVMH, in their major push into the watch industry, is looking to create a new version of the Opus Project. They have already done this with the LVRR-01 Chronographe à Sonnerie with Rexhep Rexhepi, and their recently released MB&F and BVLGARI collaboration on a new version of the Serpenti. LVMH has also taken this track with their reboot of Daniel Roth.

I am curious to see how LVMH continues to execute against this playbook - to me, LVMH doesn’t have the same draw as Harry Winston. That said, LVMH is serious about watchmaking and they are out to prove it. I am curious whether they will use Louis Vuitton as the collaboration partner, or as with MB&F work through their various brands to launch these collaborations. It only makes sense to do the larger, more prestigious collaborations with Louis Vuitton, and then smaller partnerships and collaborations through their owned brands.

That’s a story that I continue to follow - I am curious where LVMH will pop up next in the watchmaking world. My guess is that we won’t have to wait long to see as Watches & Wonders is just around the corner.

In the last couple of years, we have seen some young watchmakers launch a brand with their name based on their school watch from watchmaking school. The goal is to develop it as a souscription series to launch their brand on social media, going directly to producing watches under their own name. With social media the ability to follow this route is greatly enhanced, but this method is not yet time tested, so we will see how this generation of watchmakers traveling this path fare over the next decade.

I do think this is the new way to get out of the traditional confines of the watch industry. Rather than go work for another brand, work in a concept development workshop, or train alongside others, perhaps this is the modern way of escaping the confines of the industry like Renaud and Papi.

Social Media and the internet didn’t exist in 1986 when Renaud and Papi set out to launch their workshop, but with access to collectors around the world through social platforms, in some sense it is easier than ever to launch a souscription and to begin your career as an independent watchmaker. But it’s also more complicated than ever - there’s more competition, there’s pressure to deliver, to ensure quality across the entire range of your souscription pieces, and the pressure to have a follow up watch ready to be launched following the delivery of souscription pieces. Add that to the pressure of being the next F.P. Journe and it is an environment that is inviting and paradoxically toxic.

The environment for independent watchmaking seems more willing than ever to take a chance on a new watch or watchmaker. Those who succeed in the era of social media will be tested in their skills as a business operator and marketer as well as their skills as a watchmaker.

As with those who came before them those who end up as independent watchmakers do so because they have an endless curiosity. They believe things could be done better than they currently are, and that makes it hard to stay in a job where you disagree with manufacturing processes, or the status quo.

You don’t have to look further than today’s modern independent watchmakers to see the curiosity, the exploration, and the ingenuity in their watchmaking. I hope that this trend continues and looking to the future, there seems to be a lot to look forward to.

As ever, thank you for reading and thank you for sharing this post with anyone who might be interested or who is at least a little watch curious, or wants to understand more of the historical context of independent watchmaking.

My approach is to tell stories of watchmaking, particularly independent watchmaking, and share insights, interviews, and thoughts on how the market and the industry are eveolving. If you are new here, I’d love it if you would subscribe, and if you are already a subscriber it would mean the world to me if you would pledge your support - every subscriber and comment fuels me to keep writing, and I look forward to sharing content with you all every week.

fascinating story!

Nicely done.